The Shining Re-Released: 46 Years Later, We Finally Understand Jack's Madness

Kubrick's 1980 horror classic The Shining returns to theaters after 46 years. Modern workers see their own workplace struggles reflected in Jack Torrance's descent into madness. Why does this film still resonate so deeply?

Walking out of the theater, I overheard a guy in a plaid shirt telling his girlfriend: “I get Jack now.”

She looked confused. “You understand a guy who tried to axe-murder his wife and kid?”

“No,” he said. “I understand feeling trapped.”

That might be the most striking audience reaction I’ve witnessed since The Shining’s re-release. Forty-six years ago, people watched this film to be scared. Today, we watch it to feel understood.

A Writer’s Workplace Nightmare

Let’s reexamine Jack Torrance’s situation: a talented but struggling writer takes a job as winter caretaker at a remote hotel to support his family. The location is completely isolated. The duration is an entire winter. The job description is essentially—do nothing, just keep the place running.

Sound familiar?

“Just keep the system running.” “Just hit your KPIs.” “Just sit at your desk for eight hours.”

Jack takes the job full of confidence. He tells his boss that isolation won’t be a problem—he’ll use the time to write. There’s something painfully familiar in his eyes: that naive optimism of “I can balance work and my dreams.”

Kubrick spends nearly forty minutes building toward Jack’s breakdown. No ghosts. No blood. Just a man sitting at a typewriter, hammering out the same sentence over and over:

“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.”

Hundreds of pages of it. When Wendy flips through that stack of paper, I heard someone in the theater gasp. Not from horror—from recognition.

We’ve all been there. Staring at a blank screen, fingers hovering over the keyboard, unable to produce anything. Then the doubt creeps in. Doubt about your abilities. Doubt about why you chose this path in the first place.

Jack’s madness doesn’t begin when he sees ghosts. It begins when he realizes he can’t write anything at all.

The Overlook Hotel: A Perfect Workplace Metaphor

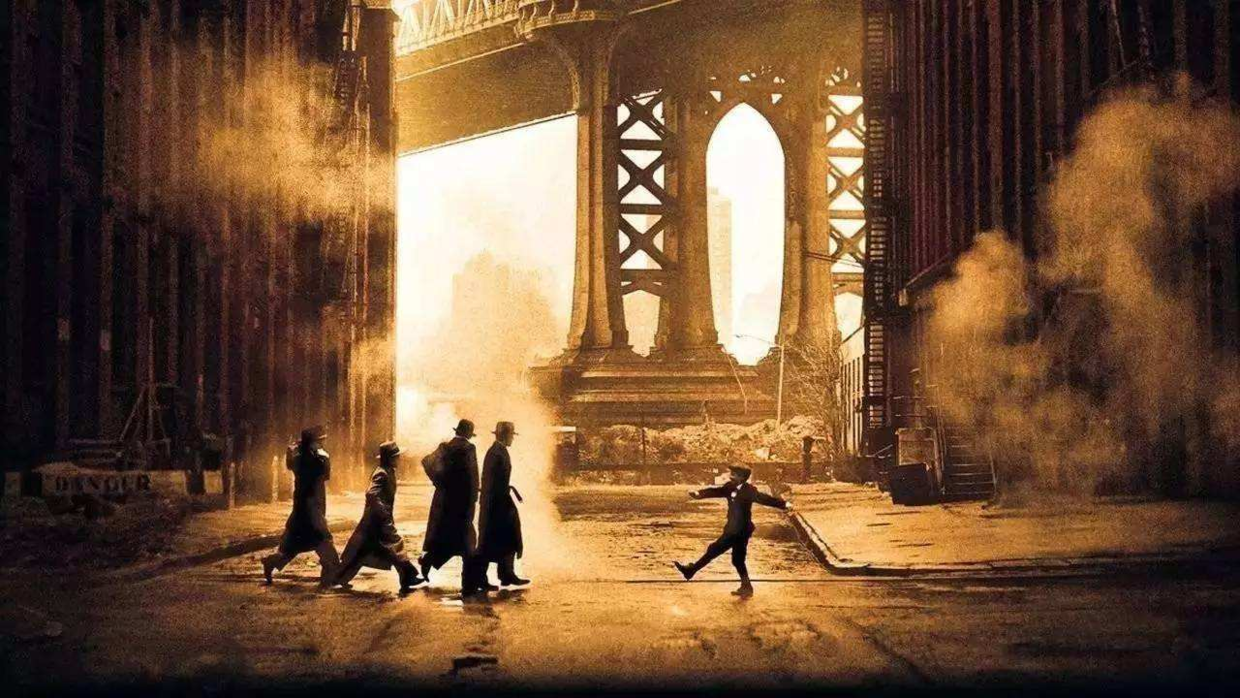

Kubrick’s choice of the Overlook Hotel as the setting was no accident.

The hotel was built on an Indigenous burial ground—cursed land, buried history. It’s magnificent but empty. The corridors seem endless, the room layouts disorienting.

Film enthusiasts have studied the hotel’s spatial structure and found it physically impossible. Windows appear where they shouldn’t. Room positions don’t match corridor lengths. Kubrick did this deliberately—creating a sense of wrongness, an instinctive unease from spatial impossibility.

It reminds me of modern office buildings. Those gleaming towers with their constant temperature, perpetual fluorescent lighting that erases the difference between day and night. You can spend an entire day inside and never shake the feeling that something’s off.

The Overlook’s true horror isn’t that it’s haunted. It’s that it’s a perfect closed system—it meets all your needs while stripping away all your freedom.

Jack has food, shelter, heating, and “time to create.” But he has no choice to leave. Snow blocks the roads. He’s trapped.

You have a salary, benefits, “stable employment.” But you have no choice to leave either. Mortgage, car payments, kids’ tuition—you’re equally trapped.

The Twins in the Hallway

“Come play with us, Danny. Forever and ever and ever.”

This shot is one of The Shining’s most iconic images. Two girls in blue dresses standing at the end of a corridor, inviting Danny to “play.”

For 46 years, people have interpreted this scene countless ways. Some say the twins symbolize death’s seduction. Others say they represent suppressed childhood memories. Some argue they’re manifestations of the hotel itself.

But I recently encountered a new interpretation on social media:

“The twins represent former employees who ‘died’ here. They were once living people with their own lives and dreams. But they stayed too long and became part of the hotel. When they invite Danny to play, they’re really saying: Join us. Become one of us. Stay here forever.”

That interpretation sent chills down my spine.

Every new hire gets that look from veteran employees. There’s envy in their eyes—envy of your dreams, your drive, your belief that anything is possible. But there’s something else too, something that seems to say: “Just wait. You’ll become like us eventually.”

Forever and ever and ever.

Jack’s Axe: When Repression Explodes

The film’s climax has Jack grabbing an axe and hunting his wife and son.

This scene has been imitated by countless horror films, but none achieve the original’s impact. Jack Nicholson’s contorted face, that line “Here’s Johnny!”—they’ve become part of pop culture.

But that’s not what I want to discuss.

I want to talk about the moment before Jack swings the axe. He’s standing outside the bathroom door with a strange smile. It’s not anger. It’s not madness. It’s something like… relief.

Yes, relief.

He finally doesn’t have to pretend anymore. Doesn’t have to pretend he’s a good husband, good father, good writer. Doesn’t have to pretend he can handle everything, endure everything. He can finally release everything he’s been suppressing.

Kubrick uses extensive symmetrical framing throughout the Overlook. The corridors are symmetrical. The lobby is symmetrical. Even the twins are symmetrical. This symmetry creates a suffocating sense of order—everything in its place, everything under control.

But humans aren’t machines. We can’t maintain symmetry and order forever. When pressure builds enough, explosion is inevitable.

Jack’s axe isn’t just aimed at that door. It’s aimed at everything constraining him—family responsibility, social expectations, his unfulfilled dreams.

I’m not defending Jack’s actions. Violence is never the answer. But I understand the feeling of being pushed to the edge. I understand what someone might do when they’ve been trapped too long.

Wendy: The Overlooked Character

When discussing The Shining, everyone talks about Jack. Few discuss Wendy.

Shelley Duvall’s Wendy has long been considered a “weak” character. She’s always crying, always screaming, always running. Many critics dismissed her as too passive.

But rewatching recently, I see it differently.

Wendy isn’t weak. She’s aware.

When Jack starts acting strangely, Wendy notices first. When Jack says “everything’s fine,” Wendy knows nothing’s fine. She tries to communicate with her husband, tries to understand what’s happening, tries to find a way out of this absurd situation.

She fails. But she never gives up.

In the end, Wendy escapes with Danny. Jack is trapped in the maze, frozen in the snow.

Some call this a “woman defeats evil” story. I disagree. Wendy didn’t defeat evil—she defeated the man she once loved. She had to watch her husband become a monster, had to grab a knife to protect herself and her child, had to make the hardest choice in the final moment—abandon Jack and flee.

That’s the real horror. Not ghosts. Not blood. Watching someone you love become unrecognizable.

Why We’re Still Watching The Shining 46 Years Later

When The Shining premiered in 1980, reviews were mixed. Critics found it “not scary enough,” “too slow,” “confusing.” Audiences wanted jump scares, not slow-burn psychological horror.

But time proved Kubrick right.

This film resonates 46 years later not because it’s terrifying. It resonates because it captures a universal human condition—the feeling of being trapped.

Jack is trapped in the Overlook, trapped by the responsibility of providing for his family, trapped by dreams he can’t fulfill.

We’re trapped in our cubicles, trapped by mortgages we can’t pay off, trapped by the fantasy that “things will get better if we just hang on.”

Social media spawned a hashtag claiming The Shining predicted modern workplace culture. It sounds like a joke, but think about it—it’s not far off.

Kubrick predicted 2026’s work culture in 1980. He knew that when someone stays trapped long enough, when their dreams are ground down by reality bit by bit, when they realize they’ll never escape that hotel—

They either break down or become part of the building.

Forever and ever and ever.

The Way Out of the Maze

The film’s final shot shows a 1921 photo from an Overlook ball. Jack stands in the center, smiling.

This shot has countless interpretations. Some say Jack was always part of the hotel—a reincarnation story. Some say his soul is trapped there forever. Others see it as metaphor: Jack chose to stop fighting and merged with the system.

Regardless of interpretation, one thing is certain: Jack never escaped the maze.

Wendy and Danny did. They paid a price, but they survived.

Perhaps that’s The Shining’s final lesson. The maze has an exit. The Overlook can be escaped. The question is whether you’re willing to abandon certain things—things you thought mattered but were actually keeping you trapped.

Easier said than done, of course.

But at least after watching this film, we know one thing: if you find yourself typing the same sentence over and over, if you’re becoming more like Jack sitting at that typewriter—

Maybe it’s time to stand up, leave that desk, and walk out of that hotel.

Before it makes you part of itself.

My Rating: 9.5/10

Strengths: Kubrick’s visual language, Jack Nicholson’s performance, timeless themes Weaknesses: Pacing may feel slow to modern audiences in certain scenes

If you enjoyed this film, also watch:

- Mulholland Drive - David Lynch’s nightmare aesthetics

- Black Swan - Another story about being trapped

- Hereditary - A new benchmark in modern horror

- Doctor Sleep - Danny’s story continues