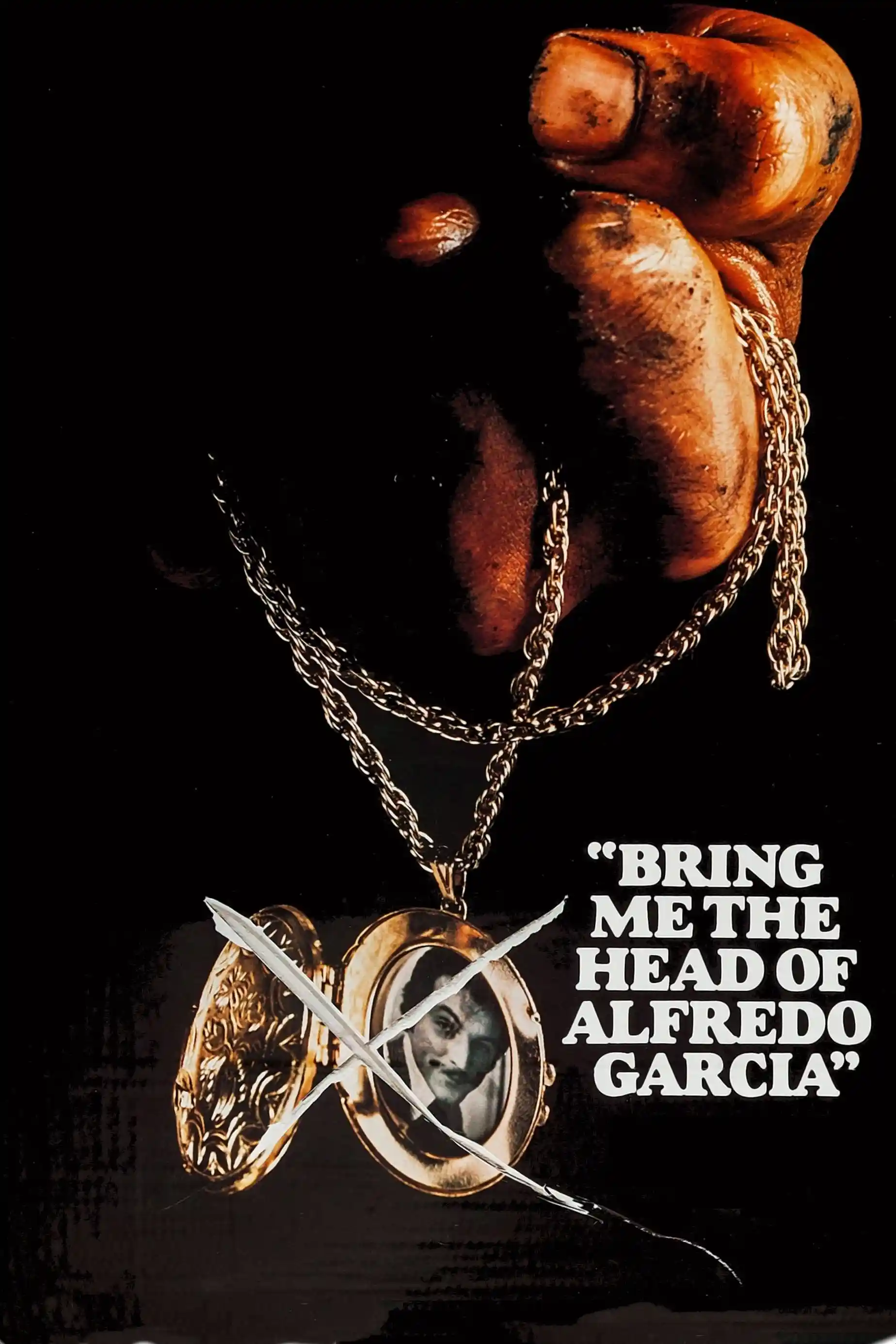

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974): Sam Peckinpah's Most Personal Apocalypse

A washed-up piano player in Mexico pursues a severed head through a desert of greed and death. Peckinpah's most reviled and most revealing film—a masterpiece of self-destruction.

There’s a shot in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia that tells you everything: Warren Oates driving through the Mexican desert, flies buzzing around the burlap sack next to him, talking to the decaying head inside as if it were his only friend. The head doesn’t answer. The flies keep buzzing. The car keeps moving toward something that might be salvation but is definitely death.

Sam Peckinpah made Alfredo Garcia at the bottom of a spiral. His career was in ruins after Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid was recut by the studio. He was drinking heavily. His marriages had failed. He poured all of it into this film—and what came out is the rawest, most uncompromising work of his career.

The critics despised it. The audience stayed away. But Peckinpah called it “the only film of mine where I had total creative control.” For better or worse, this is pure Peckinpah.

The Setup: A Bounty on the Dead

A Mexican crime lord’s daughter is pregnant. The father is Alfredo Garcia, a now-dead playboy. The crime lord puts a bounty on Garcia’s head—literally. He wants the head brought to him.

This bounty ripples down through layers of Mexican society until it reaches Bennie (Warren Oates), a washed-up American piano player in a seedy Tijuana bar. Bennie knows Garcia is dead—his girlfriend Elita (Isela Vega) was having an affair with him. All Bennie has to do is dig up the grave and collect the head.

Easy money. Except nothing in Peckinpah’s world is easy.

Warren Oates: Peckinpah’s Surrogate

Oates was Peckinpah’s most frequent collaborator, and in Bennie he created the director’s clearest self-portrait. Bennie is a man who was probably talented once, who’s been ground down by life, who uses alcohol and dark glasses to shield himself from a world he can’t handle.

The famous sunglasses never come off. Oates insisted on this—they’re prescription, they’re part of Bennie, and they create a permanent barrier between him and reality. When he finally removes them near the end, it’s a stripping away of defense. He’s ready to die.

Oates plays Bennie as a man who’s already lost everything except the chance to lose with dignity. When Elita is killed, when the head is stolen, when every betrayal compounds—Bennie doesn’t rage against injustice. He just keeps going, driven by something beyond logic.

The Road Trip From Hell

The middle section of Alfredo Garcia is a road movie with a corpse. Bennie and Elita drive through the Mexican countryside, argue, reconcile, stop at a picnic spot where they’re attacked by rapists—a scene of horrifying violence that Peckinpah refuses to make cathartic.

This interlude is where the film’s critics check out. It’s slow. It’s ugly. The violence against Elita is disturbing in a way that feels gratuitous.

But Peckinpah is setting up his thesis: Mexico in this film is a place where violence is casual, where American money corrupts everything, where a woman’s body and a dead man’s head are both commodities. The picnic scene isn’t exploitation—it’s the film’s thematic heart, showing how violence begets violence, how Bennie’s “simple” job requires swimming through a sewer.

The Head as Character

After Elita’s death, Bennie retrieves the head and begins his grim journey to collect payment. But the sack becomes his companion. He talks to “Al.” He apologizes to him. He drinks with the head propped up next to him.

This would be black comedy in another film. In Alfredo Garcia, it’s genuinely affecting. Bennie has no one left. His girlfriend is dead. Everyone wants to steal his prize. The severed head becomes his only constant—the one “person” who won’t betray him.

“You’re my meal ticket, Al,” Bennie tells the head. “I’m taking you back.”

The Ending: No Survivors

⚠️ Spoiler Warning: Full discussion of the ending follows.

Bennie delivers the head. He gets his money. And then, staring at the crime lord who put everything in motion, he opens fire.

The massacre that follows is Peckinpah’s most nihilistic. Bennie kills everyone—guards, the crime lord, anyone in his way. He walks out of the compound, head under his arm, money in his pocket, and drives away.

He doesn’t make it far. A roadblock appears. Soldiers open fire. Bennie dies behind the wheel, the head rolling across the desert floor.

There’s no transcendence here. No triumph. Bennie got his revenge, and it meant nothing. The money means nothing. The head means nothing. It’s Peckinpah’s bleakest statement: in a world built on greed and violence, the only escape is death.

Peckinpah’s Vision: Mexico as Mirror

Mexico in Alfredo Garcia isn’t the real Mexico—it’s Peckinpah’s psychic landscape. The dusty towns, the corrupt police, the endless roads going nowhere—these are projections of American guilt and self-destruction.

Peckinpah loved Mexico and hated what Americans did to it. The crime lord’s wealth comes from American industry. The bounty hunters are Americans exploiting Mexican desperation. Bennie is an American who’s escaped to Mexico only to be destroyed by American greed reaching into his refuge.

It’s not subtle. But Peckinpah was beyond subtlety by this point. He was making films like a man dying—which, in a sense, he was.

Critical Reception and Cult Status

Alfredo Garcia was savaged on release. Roger Ebert gave it zero stars, calling it “some kind of strange, horrifying masterpiece.” The audiences agreed—or disagreed—staying away in droves.

But the film found its defenders. Critics who dismissed it in 1974 reconsidered. Quentin Tarantino called it “flawless.” Guillermo del Toro champions it. The reputation has grown as Peckinpah’s career has been reassessed.

What seemed like excess in 1974 now looks like honesty. Peckinpah wasn’t trying to make a commercial film. He was exorcising demons. The result is too raw for casual viewing—but for those who can handle it, it’s extraordinarily powerful.

My Rating: 8.5/10

What works:

- Oates gives the performance of his career

- Peckinpah’s uncompromising vision

- Mexico as existential landscape

- The man-and-head relationship is strangely moving

- Ending that pulls no punches

What doesn’t:

- Violence against women is hard to watch

- Pacing in the middle section drags

- Unrelenting bleakness may exhaust viewers

If You Liked This, Try:

- The Wild Bunch (1969) — Peckinpah’s earlier Mexican apocalypse

- Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) — Peckinpah’s elegiac western

- Bad Lieutenant (1992) — Ferrara’s similarly uncompromising descent

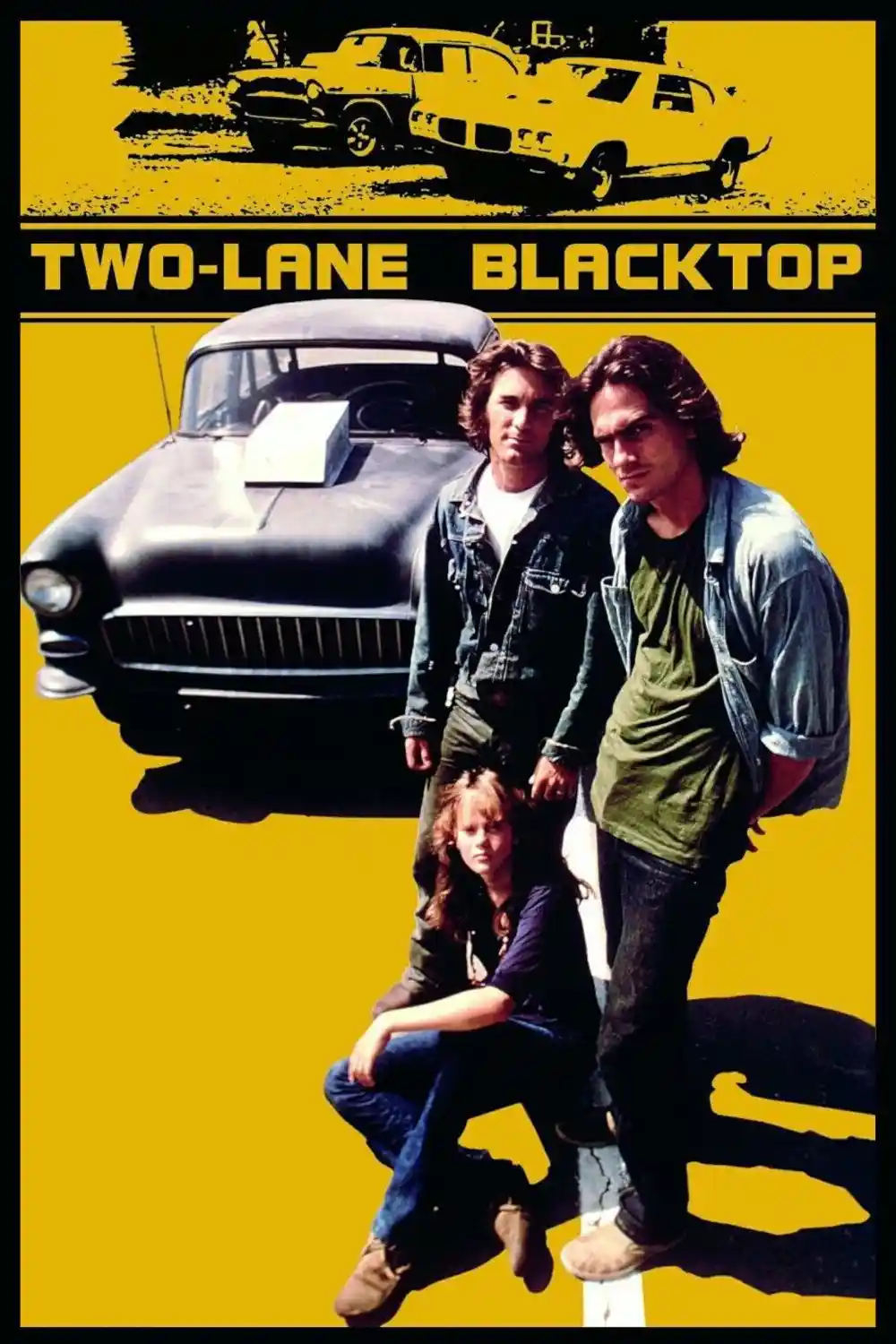

- Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) — Another existential road movie

- El Topo (1970) — Jodorowsky’s surreal Mexican western

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia is not a film I recommend lightly. It’s ugly, violent, and deliberately unpleasant. It asks you to follow a desperate man on a journey that can only end in death.

But if you can handle it, there’s something true here—about greed, about violence, about the American myth of easy money. Bennie dies with a severed head and a bag of cash, and neither means anything.

That’s Peckinpah’s final message: in the end, the head and the money are just things. What matters is how we live—or how we fail to.

References

- Weddle, David. If They Move… Kill ‘Em!: The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah, Grove Press, 1994

- Seydor, Paul. Peckinpah: The Western Films—A Reconsideration, University of Illinois Press, 1997

- Ebert, Roger. Original review (0 stars) and later reassessment

- Tarantino, Quentin. “Peckinpah’s masterpiece,” interview clips

- Simmons, Garner. Peckinpah: A Portrait in Montage, University of Texas Press, 1982