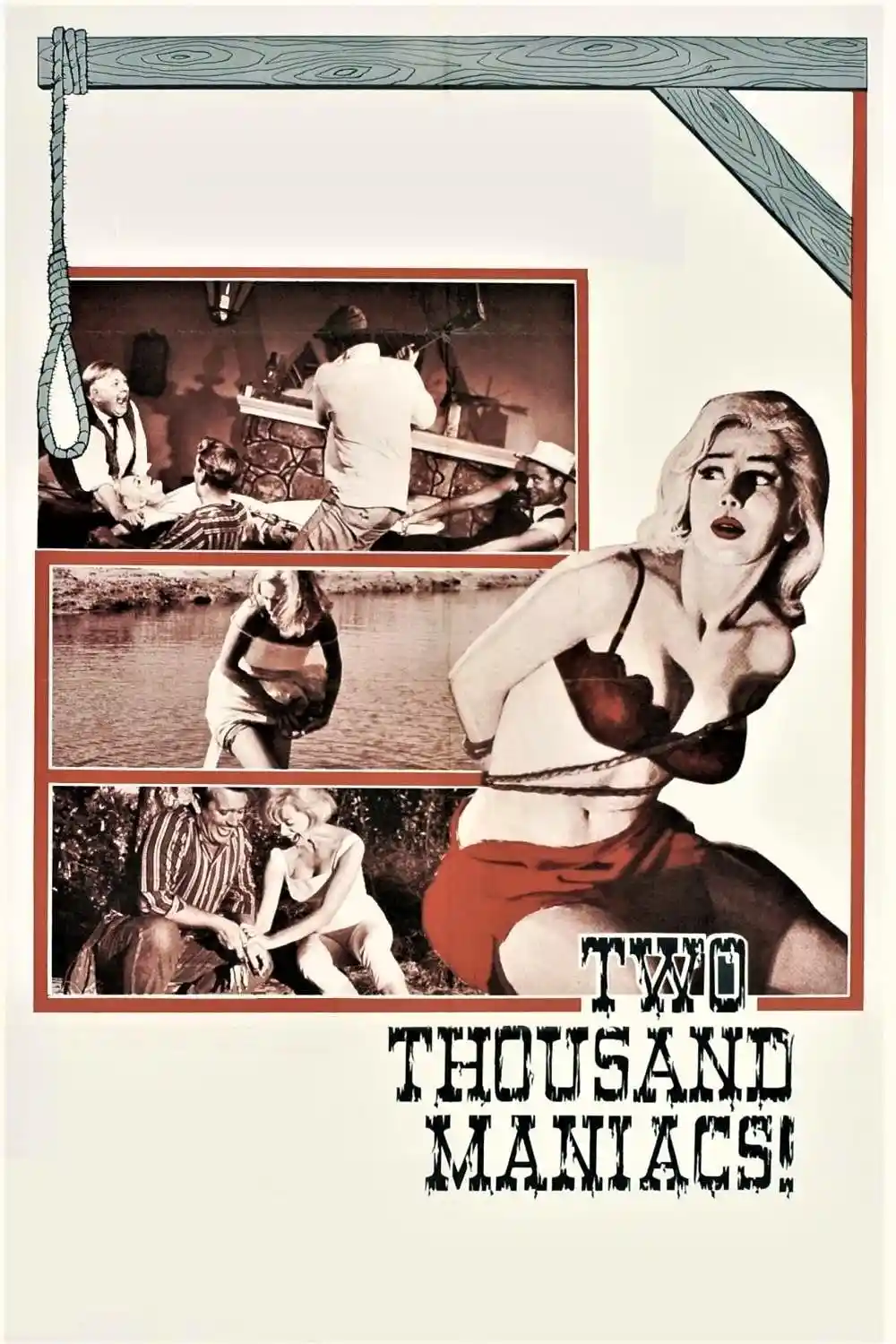

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964): The Blood-Soaked Birth of American Gore Cinema

Herschell Gordon Lewis's Confederate revenge fantasy launched the splatter film genre. Sixty years later, it still has the power to disturb—just not for the reasons you'd expect.

I want to be upfront about something: Two Thousand Maniacs! is not a good film by any conventional measure. The acting ranges from wooden to embarrassing. The pacing is erratic. The technical craft is what you’d expect from a $65,000 production shot in two weeks. And yet, I’ve now seen it four times, I’ve written about it twice, and I think about it more than films that are objectively superior in every way.

What is it about Herschell Gordon Lewis’s 1964 drive-in shocker that keeps drawing me back? Part of it is historical importance—this is one of the founding documents of the splatter film genre, the movie that proved audiences would pay to see explicit on-screen violence. But there’s something else here, something that makes Two Thousand Maniacs! feel stranger and more unsettling than its reputation as a goofy gore flick would suggest.

This is a film about the Civil War that’s still being fought. About wounds that won’t heal. About American violence dressed up as Southern hospitality. And while I don’t think Lewis intended half of what I’m about to argue, the text is there if you’re willing to look.

The Godfather of Gore

Before we get into the film itself, we need to talk about Herschell Gordon Lewis. The man was not a horror fan. He wasn’t particularly interested in cinema as art. He was a marketing professor and exploitation filmmaker who had been making “nudie cuties” (softcore nudist camp films) when he realized that market was getting saturated.

His business partner David F. Friedman had an insight: audiences wanted to see things they couldn’t see anywhere else. In the early 1960s, violence was that taboo. The Hays Code was still nominally in effect, and mainstream Hollywood wouldn’t show explicit bloodshed. Lewis and Friedman decided to fill that gap.

Blood Feast (1963) was their first horror effort—a cheaply made Egyptian-themed slasher that featured the first real “gore” scenes in American cinema. It was crude, almost comically so, but audiences responded. They screamed. They fainted. They came back for more.

Two Thousand Maniacs! was the follow-up, and Lewis decided to make something more ambitious: a full narrative with characters, tension, and a revenge plot that would give context to the carnage.

The Premise: Southern Discomfort

Six Northern tourists are detoured into Pleasant Valley, Georgia, a small town celebrating its centennial. The townspeople are aggressively friendly—almost comically so, with their exaggerated accents and constant offers of hospitality. The travelers are told they’re the “guests of honor” at the celebration.

You can probably guess where this is going.

Pleasant Valley was destroyed by Union troops exactly one hundred years ago. The entire population was massacred. Now, on the anniversary, the town returns—ghosts? supernatural manifestation? the film never quite explains—to take revenge on six random Yankees.

What follows is a series of increasingly creative murders:

| Victim | Method | Screen Time |

|---|---|---|

| First couple | Man dismembered, woman in barrel of nails rolled downhill | Extensive |

| Third victim | Drawn and quartered by horses | Brief but effective |

| Fourth victim | Boulder dropped on torso | Quick |

| Survivors | Escape | Unclear fate |

The violence, by modern standards, is obviously fake—bright red paint for blood, mannequin limbs, visible cuts between “impact” and “aftermath.” But in 1964, nobody had seen anything like it. Audiences reportedly vomited. Some theaters had nurses on standby.

What Lewis Got Right (Accidentally?)

Here’s where things get interesting. Lewis was making a product, not a statement. He’s said repeatedly in interviews that he had no artistic pretensions—he wanted to make money, and gore was the gimmick. But Two Thousand Maniacs! works on levels that its creator didn’t intend.

The South as Wound

The premise—a Confederate town returning to murder Yankees—is played for horror-comedy in the film. The townspeople are buffoons with silly accents, their cruelty cartoonish. But underneath that goofiness is something genuinely disturbing: the idea that the Civil War never ended, that Southern grievance is eternal, that given the chance, the violence would resume.

Lewis shot this in 1964. The Civil Rights Movement was at its peak. Freedom Riders had been beaten and murdered in the South. Churches were being bombed. The Klan was resurging. Whether Lewis intended it or not, his “comedy” about Southerners murdering Northerners landed in a very specific historical moment.

Hospitality as Trap

The townspeople’s relentless friendliness is genuinely unsettling—more so than the violence, honestly. Every “y’all come back now” and “bless your heart” carries an undertone of menace. This plays on a real anxiety about regional difference, about not knowing the codes, about being the outsider in a place with its own rules.

The tourists can’t leave because they don’t understand they’re in danger. The hospitality isn’t despite the violence—it’s part of the same system. You’re the guest of honor at your own murder.

The Centennial Framework

Setting the film during a “centennial celebration” links it explicitly to commemorative culture—the reunions, monuments, and rituals through which the South processed (or avoided processing) the Civil War. These celebrations often whitewashed the Confederacy, reframing the war as a noble lost cause rather than a defense of slavery.

Lewis’s fictional Pleasant Valley takes this logic to its extreme: if the war was just, then revenge is just. If the cause was honorable, then honoring it requires action. The centennial isn’t about memory—it’s about continuation.

The Craft (Such As It Is)

Let me be honest about the technical realities here. Two Thousand Maniacs! was shot in fourteen days in St. Cloud, Florida. The “town” was a real main street that Lewis dressed with Confederate flags. The cast was mostly local non-actors mixed with a few exploitation film veterans.

What works:

- The opening sequence, with its banjo theme song (written and performed by Lewis himself) and road signs directing victims to their doom, is genuinely effective low-budget filmmaking

- Some of the murder setpieces are cleverly staged given the budget constraints

- The cheerful tone creates legitimate dissonance with the violence

- The location shooting gives it an authenticity that studio work wouldn’t have

What doesn’t:

- The acting is dire, with characters existing only to die

- The middle section drags badly

- The “twist” ending is nonsensical

- Technical gaffes are constant (shadows, equipment visible, continuity errors)

But here’s the thing: none of that matters for what Lewis was doing. This wasn’t meant to be watched closely. It was meant to be experienced in a drive-in, half-watched between make-out sessions, memorable for its money shots of violence rather than its coherent narrative.

The Theme Song Problem

I need to talk about “The South’s Gonna Rise Again,” the banjo song that plays over the opening credits and recurs throughout the film. Lewis wrote it as a joke—a hummable tune that would stick in audiences’ heads, good marketing.

But listen to the lyrics:

“The South’s gonna rise again! The South’s gonna rise again!”

Sung cheerfully, repeatedly, over images of Confederate flags and smiling townspeople preparing for murder.

In 2024, after Charlottesville, after the Confederate monument debates, after “heritage not hate” revealed itself as exactly what critics always said it was, this song hits differently. What was supposed to be campy now sounds like a threat. The joke aged into prophecy.

I don’t think Lewis meant anything by it. But art doesn’t care about authorial intent. The text says what it says.

Influence: The Splatter Legacy

Two Thousand Maniacs! spawned a genre. Not single-handedly—Blood Feast came first, and Italian giallo films were developing simultaneously—but this film proved that explicit gore could sustain a feature-length narrative.

The lineage runs through:

- Last House on the Left (1972) — Craven’s rape-revenge film owes much to Lewis’s formula

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) — Another vision of the Southern grotesque

- I Spit on Your Grave (1978) — Pushed the revenge narrative further

- Hostel (2005) — Eli Roth explicitly cited Lewis as an influence

- The House That Jack Built (2018) — Von Trier playing in the same sandbox

Lewis himself kept making gore films through 1972, then retired to become a successful direct marketing consultant. He returned briefly in 2002 for Blood Feast 2, proving you can go home again—even if home is a Florida sound stage soaked in corn syrup.

The Remake (And Why It Matters)

In 2005, Tim Sullivan remade Two Thousand Maniacs! as 2001 Maniacs, starring Robert Englund. It’s a better-made film technically—higher production values, better actors, more explicit violence. It’s also less interesting.

Sullivan understood the gore but missed the strangeness. His Pleasant Valley is a self-aware horror movie setting; Lewis’s Pleasant Valley is a nightmare of American regionalism. The remake is a theme park; the original is a bad dream you can’t quite remember in the morning.

This is often the case with exploitation cinema. The cheapness, the desperation, the corner-cutting—these produce an energy that polished remakes can’t capture. Two Thousand Maniacs! feels like it shouldn’t exist, like it crawled out of some fever swamp of American cinema. That’s part of its power.

Moral Questions

I need to address the obvious: is it ethical to enjoy this film?

The violence is cartoonish enough that I don’t think it poses a “harmful content” issue in the usual sense. But the Confederate imagery, the “South rises again” messaging, the racialized revenge fantasy—these are genuinely troubling elements, even if Lewis didn’t intend them as ideology.

My approach: watch it as a historical document, be aware of what it’s doing (intentionally and not), and recognize that “important” doesn’t mean “good” or “unproblematic.” Birth of a Nation is important too. Importance isn’t endorsement.

My Rating: 6/10

As a film:

- Historically significant but technically poor

- Moments of genuine inspiration buried in amateurism

- Theme song will haunt your nightmares

- More interesting to think about than to watch

As cultural artifact:

- Essential viewing for horror historians

- Fascinating window into 1960s exploitation cinema

- Accidentally prophetic about American regional violence

- Starting point for understanding the splatter genre

If You Liked This, Try:

- Blood Feast (1963) — Lewis’s first gore film, even cruder

- Spider Baby (1967) — Another 60s horror with Southern Gothic vibes

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) — The form perfected

- Deliverance (1972) — “Civilized” version of the same anxieties

- Tucker and Dale vs. Evil (2010) — The premise inverted and made comedic

Two Thousand Maniacs! is not a film I recommend lightly. It’s crude, offensive in ways both intentional and accidental, and tedious in stretches. But it’s also a window into American anxieties that we’re still processing, a document of what audiences in 1964 would pay to see, and the unlikely origin point for a genre that would shape horror cinema for decades.

The South did rise again, in a sense—not as Lewis imagined, but in ways his film accidentally predicted. Pleasant Valley is still out there, waiting for the next centennial, the next group of outsiders who don’t know the local rules.

Y’all come back now, hear?

References

- Lewis, Herschell Gordon. Interview, Fangoria, 1982

- Friedman, David F. A Youth in Babylon, Prometheus Books, 1990

- Muir, John Kenneth. Horror Films of the 1960s, McFarland, 2007

- “‘2000 Maniacs!’ Is The Unrepeatable Dawn of Gore,” Dread Central, 2023

- The Herschell Gordon Lewis Collection, Something Weird Video (restoration notes)

- McCarty, John. Splatter Movies: Breaking the Last Taboo, St. Martin’s Press, 1984